Do you still believe in noble savages? Scientists will disappoint you.

Did you imagine primitive people as kind-hearted hippies who shared everything equally and lived in harmony? Anthropologists have destroyed this beautiful fairy tale. It turns out that even in the Stone Age, people were... people.

For centuries, philosophers and anthropologists have admired hunter-gatherer societies, considering them a model of justice and mutual aid. This image of the "noble savage" has inspired philosophers and writers for centuries. But modern anthropologists say it's time to wake up. Behind the façade of equality in hunter-gatherer societies lies a cunning game of interests, where everyone fights for their own piece of the action. Let's explore how scientists have broken this stereotype and what they've actually discovered.

The Age of Enlightenment gave the world the dream of a "natural man"—free from the vices of civilization. The French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau, one of the main proponents of this idea, argued that civilization only corrupts, while true virtue lies in pristine simplicity. His ideas influenced literature: recall Daniel Defoe's Robinson Crusoe, where "savages" are portrayed as noble and honest.

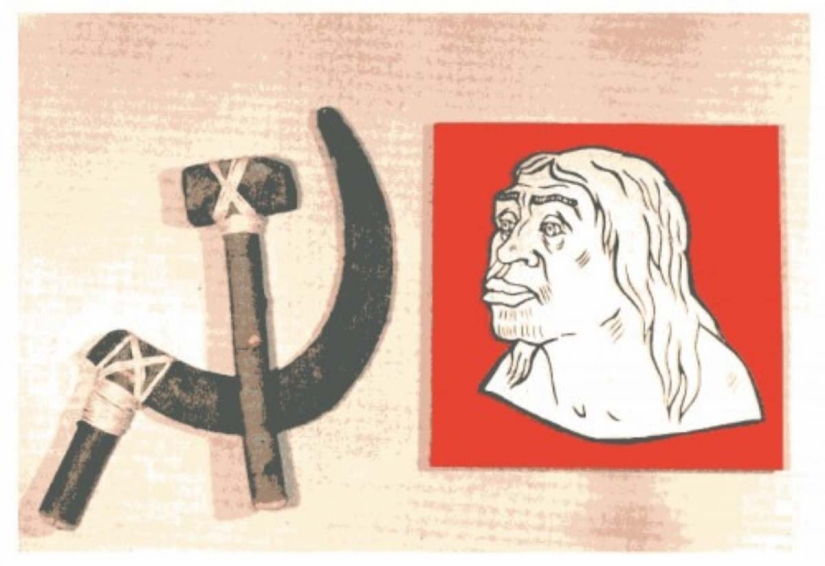

By the 19th century, this myth had become scientific. Expeditions brought back stories of "primitive" peoples, and Europeans eagerly applied their own romantic lens to them. Friedrich Engels, a close associate of Karl Marx, even saw hunter-gatherers as a model of "primitive communism." He wrote that in such societies, everything is shared, and decisions are made based on kinship and mutual assistance—without classes or the state.

Interestingly, Engels drew on data from tribes like the Iroquois in North America, where women did have a strong influence on resource distribution, which supported the vision of gender equality.

But the reality turned out to be more complex. Hunting and gathering ruled the roost for about 95% of human history—until the Neolithic Revolution 10,000 years ago. For centuries, anthropologists viewed these societies as a "window into the past." However, recent analysis shows that equality is not the norm, but a subtle balance of power.

Anthropologists Duncan Stibbard-Hawkes of Durham University and Chris von Rueden of the University of Richmond sifted through reams of ethnographic data. Their conclusion, published in the journal Behavioral and Brain Sciences, is simple: true egalitarianism—equality of opportunity and goods—does not exist in any studied hunter-gatherer society. Apparent equality is the result of pressure, selfishness, and the struggle for freedom, not altruism.

Take the sharing of spoils. It seems like the hunter gives away meat to everyone out of pure kindness. But in reality, it's a way to avoid annoying requests and reproaches. Among the Kung tribes in South Africa, for example, a third of conversations are complaints about greedy neighbors. About 34% of daytime conversations revolve around the question, "Why didn't you share?" The hunter distributes food to maintain peace, not out of love for his neighbor.

Another example is the Mbendjele of Congo. They have a ritual called "mosambo": the aggrieved party gathers everyone and loudly complains about the "big man" who is being arrogant. This isn't about justice, but about preventing anyone from seizing power. Such practices keep potential leaders in check, but behind them lies not harmony, but constant vigilance.

And the hierarchy? It exists, but it's hidden. Status is conferred not by wealth, but by usefulness and modesty. Among the Tsimane in Bolivia, those who help everyone and don't brag are respected. The best hunter can become an authority if they are fair and cooperative. It's like an unspoken competition: whoever proves themselves to be the "most moral" rises to the top.

What appears to be harmonious cooperation from the outside is in fact a constant, invisible struggle. Each tribe member fiercely defends their independence and does not allow their fellow tribesmen to rise above others. Equality here is not a manifestation of high morality, but the result of mutual restraint of selfish interests.

Von Rueden and Stibbard-Hawkes emphasize that scientists were mistaken in confusing the outcome (equal distribution) with the cause (ethics). In reality, equality is a side effect of a selfish struggle for personal independence. The myth of the "noble savage" is outdated—it's time to look deeper.

The study's findings finally lay to rest the myth of the "noble savage" living in idyllic harmony thanks to innate virtues. Equality in ancient societies turns out to be not a utopia of universal altruism, but a fragile balance of competing egoisms. Each tribe member strives for their own benefit and autonomy, and it is precisely the clash of these desires that creates the illusion of selfless cooperation.

This discovery forces a new look at the origins of human society and the nature of social equality. Perhaps the pursuit of justice in the modern world is also based less on lofty ideals than on the practical unwillingness of each person to allow others to dominate them.

Do you believe in "noble savages" or do you think selfishness is the perpetual engine of progress? Share your thoughts in the comments!

Recent articles

It's high time to admit that this whole hipster idea has gone too far. The concept has become so popular that even restaurants have ...

There is a perception that people only use 10% of their brain potential. But the heroes of our review, apparently, found a way to ...

New Year's is a time to surprise and delight loved ones not only with gifts but also with a unique presentation of the holiday ...